It’s gotten off to a later start this season, but for those of us in Western New York, the lake-effect snow season has kicked into gear. Lake-effect snow is produced when cold air moves over warmer (at least relatively) water. Heat transfer occurs at the boundary between air and water, with the lower layers of air absorbing heat from the water. That extra heat also brings water vapor from the lake’s surface. The moist warmer air rises through the colder air above. As it does the water vapor it carries freezes and falls to the ground downwind as snow.

Several factors determine the intensity of the event. First is the temperature difference between the water and the air. Simply put, bigger differences create more intense lake-effect events. Buffalo’s seven feet of lake-effect snow in 2014 was driven by arctic air blowing over warmer Lake Erie water in November. Another factor is the amount of water the wind blows over before it hits land. This distance is called fetch. A longer fetch results in more moisture being drawn up into the atmosphere and creates more snow.

The shape and elevation of the land also impacts the lake-effect snowfall. Hills and valleys play an important roll in channeling the flow of the snow giving wind. Higher hills also wring more of the moisture out of the air. The Tug Hill plateau where Lake Ontario meets the Adirondack foothills averages over 200 inches of snow a year. I’ve been to the region in the early winter and seen six feet of snow on the ground.

So how intense is the strongest lake-effect event? According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration lake-effect rates can exceed 5 inches/hour, include thundersnow and last for days. During intense events of lake-effect the blowing and falling snow often create whiteout conditions. In whiteouts it is impossible to see more than a few feet in front of you. Unlike large storm systems that effect wide areas lake-effect events are often highly localized. A typical band might be 25 miles wide and extend up to 100 miles from the shore. While snowfall within the band might be measured in feet just a few miles outside it’s borders little or no snow may reach the ground.

Though it’s called lake-effect, the same principles apply to cold air blowing over any warmer body of fresh or even salt water. In addition to the Great Lakes, Utah’s Salt Lake and bays like the Chesapeake and Massachusetts as well as the Black, Caspian, and Baltic Seas all produce snow on their downwind shores.

Today’s Map

My apologies to my Canadian readers on the leeward side of the lakes, especially on the leeward side of Lake Huron. I know those areas experience lake-effect too, but this map from the University of Illinois only lists the snowfall amounts on the US side of the lakes.

FWIW, I live in one of the green 60-100 inch areas. My town probably averages near 80. One of my salons which is 15 miles closer to the lake gets closer to 100. Lake-effect is a strange beast.

As always thanks for reading.

Armen

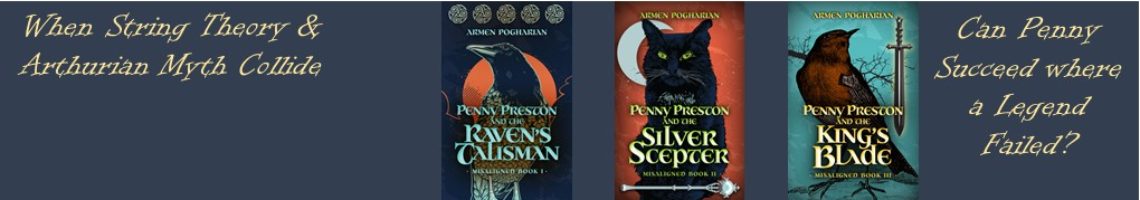

Note to pay the bills: While they’re not overtly environmental, the books in the Misaligned Series do integrate interesting environmental facts and issues into the story. Phenomenon like the migration of the monarch butterflies and lake effect snow play important roles in the first book. If that peaks your interest, check out a summary of the series here or find links to purchase books here.

The effect of the Great Lakes on our weather is, I am told, a meteorologist’s potential nightmere. The Chief Meteorologist from the US Weather Bureau office at the Rochester airport once told me (He had just arrived here from Nebraska.) “This is hard. Where I just came from, I could look out the window and predict the local weather for the next three days.” At least we have interesting weather.

I really don’t mind the snow, but then I don’t live in one of the areas none as a persistent snow belt.

Great post, Armen. Lake effect is such a normal phenomenon around here that I forget that other people don’t know what it is!

So true, Amy. My relatives all think we’re perpetually buried in six feet of snow – especially when all they hear is the national news. I often explain it to them as being a lot like thunderstorms in the summer. Some areas get drenched and others just hear the distant rumbles of thunder.