When most people hear the word oxidation, if they think of anything, they think of rust or if they’re old enough they might think of tarnished silver. Both of these are common examples of oxidation, the process by which one substance accepts or takes electrons from another. While oxygen or compounds containing it (e.g., acids) are the most common oxidizers (hence the name), other elements such as chlorine, bromine, and fluorine are also oxidizers. Commonly used as a disinfectant in swimming pools, the oxidizing properties of chlorine are what create the stiff straw-like hair that marks a competitive swimmer.

All of these examples of oxidation are slow processes taking anywhere from days to weeks or even years to manifest themselves. If you speed the process up you can achieve rapid oxidation, which produces heat, light, and other by-products. Most of us know this process as burning, or simply fire. Our distant ancestors’ control of the rapid oxidation process may very well be the single biggest contributor to the acceleration of our mental capacity. Fire allowed humans to move into colder climates, work into the dark hours, and improve tool making (burning the tips of sticks, firing clay, and eventually metallurgy). Using fire to cook food made an even greater contribution. Cooking food not only improves the taste (at least most of the time), it also eliminates parasites. More importantly, cooking breaks down the long chains of proteins in meat and softens the starches in plants. Both actions make the foods easier to digest. Easier digestion of more foods results in higher calorie diets, which leads to more energy available for bigger brains.

Even the supreme ruler of the Greek pantheon, Zeus, recognized the threat our command of fire offered. He bound Prometheus, the titan who gave humans the knowledge of fire, to a rock and sent an eagle to devour his liver. At night it grew back, only to be eaten again the next day. The myth of Prometheus evolved through time, and he became a symbol for the double-edged sword of progress. Mary Shelly’s classic story Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, is built on the concept or the fear that advances might not all be for the best. They may deliver benefits, but as Heinlein wrote in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “TANSTAAFL” or “There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch” (the phrase predates Heinlein’s use, but his book wildly popularized it). Fire is no exception.

Even the supreme ruler of the Greek pantheon, Zeus, recognized the threat our command of fire offered. He bound Prometheus, the titan who gave humans the knowledge of fire, to a rock and sent an eagle to devour his liver. At night it grew back, only to be eaten again the next day. The myth of Prometheus evolved through time, and he became a symbol for the double-edged sword of progress. Mary Shelly’s classic story Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, is built on the concept or the fear that advances might not all be for the best. They may deliver benefits, but as Heinlein wrote in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “TANSTAAFL” or “There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch” (the phrase predates Heinlein’s use, but his book wildly popularized it). Fire is no exception.

Excluding the release of greenhouse gasses from the burning of fossil fuels, the controlled use of fire has been an all-around bonanza for humans. Of course the key is the word control. Uncontrolled fires have brought great misery and suffering to humankind. In just the last 2,000 years, fires have wrought great destruction. Fire has destroyed many of the world’s great landmarks, some permanently (the library in Alexandria & the Globe Theatre), others have been rebuilt or restored (the White House & the US Patent Office – twice). Wild fires, both natural and otherwise, have also devastated thousands of acres of land. As bad as those two categories of fires are, they’re not the worst. By far the most destructive fires, in terms of direct human misery, have been the great city fires. Including fires started by natural disasters (eruptions, earthquakes, and hurricanes), war (both attacking and retreating armies) and accidents (cows, bakeries, and industry) hundreds of cities have been ravaged by ‘great’ fires. Many of them have burned more than once.

Today (4 September 2013) marks the 347th anniversary of one of the most famous ‘great’ fires, London 1666. It’s actually the third ‘great’ fire in London, the others being in 1135 and 1212. Traced to a bakery on Pudding Lane, the fire actually started on 2 September. The incompetent response of Sir Bloodworth (Lord Mayor of London) and strong winds combined to turn an already major fire into an epic disaster. While the official death toll is listed as only six, the deaths of poor residents were unrecorded and the real toll may well have been in the hundreds. More devastating than the death toll, the fire destroyed over 13,000 buildings and left 70,000 of the nearly half-million city residents homeless.

Today (4 September 2013) marks the 347th anniversary of one of the most famous ‘great’ fires, London 1666. It’s actually the third ‘great’ fire in London, the others being in 1135 and 1212. Traced to a bakery on Pudding Lane, the fire actually started on 2 September. The incompetent response of Sir Bloodworth (Lord Mayor of London) and strong winds combined to turn an already major fire into an epic disaster. While the official death toll is listed as only six, the deaths of poor residents were unrecorded and the real toll may well have been in the hundreds. More devastating than the death toll, the fire destroyed over 13,000 buildings and left 70,000 of the nearly half-million city residents homeless.

So what’s all this got to do with a YA contemporary fantasy based in a mythical upstate NY town? I applied a dose of writer’s license to Celtic myth, creating the Red Leprechaun (Welsh: Coch Coblyn), a fire loving prankster that suddenly appears in the town. Two of my time-hopping characters (Mr. Myrdin & Master Poe – a scientist from the 7th dimension trapped in a raven’s body) recognize the Coch Coblyn as the entity responsible for several earlier ‘great’ fires. Their efforts to prevent another such disaster form one of the arcs of the story.

Here’s the segment where I add the Coch Coblyn (and one of my time-hopping characters) to the Great London fire of 1666:

In 1666…

Thomas Farynor looked at the small pile of wood next to the bakery’s oven and shook his head. “William!” he called out to his son.

William appeared from around the corner of the oven.

“William, we need more wood for tonight’s baking.”

“Cottage loaves tonight?” William asked.

“Of course. Tomorrow’s the first Sunday of September and you know what that means.”

“Yes, the city will be full of people going to the Feast of the Farmer at St. Paul’s.”

“Hours of listening to the good Abbot lecturing against the sins of gluttony and lust hardly qualifies as a feast to me,” Thomas said with a chuckle. “But the important thing is, those people will be hungry. A lot of ‘em are going to come down Fleet Street on their way to the bridge. And who are they going to pass at the corner of Fleet and Pudding Lane?”

“Us,” answered William.

“That’s right… hundreds of hungry souls walking right by our door. We’ll sell as many loaves as we can bake. By stacking the dough into cottage loaves, we can make twice as many loaves and still sell ‘em for the same price as regular ones,” he said with a twinkle in his eye. “But we need a hotter oven. And for that we need more wood.”

“Father, it’ll take me half the night to bring in that much wood. Who will help you knead the dough and stack the loaves?”

“Good point, son. Wake our boarder Myrdin and have him help you bring in the wood. If he complains, promise him an extra loaf in the morning.”

“The old journeyman who claims to have once been a master carpenter?” William asked with a hint of disdain.

“Don’t be so harsh, son. He did an excellent job repairing the cooling shelves; saved us half a shilling and several days of lost baking. Certainly a fair bargain for a few nights on the floor of the storehouse, don’t you think?”

“I suppose you’re right.”

Smiling at his son, “Remember, any man can have a turn of bad luck, and someday it may be you who needs the charity and grace of another. Now be quick about it, so you have time to help me with the baking. I’ll even let you make your own loaves.”

William smiled back at his father and disappeared around the corner. He hadn’t been gone for a minute when Thomas heard the loud banging of wood on the door. He quickly added some larger kindling to the fire and walked to the door. He opened it, expecting to find his son or the journeyman bearing an armload of firewood, but was surprised to see a small disheveled man dressed in red leaning on a gnarled walking stick. What an odd time of night for a beggar, thought Thomas.

“Pardon me, sir, for the lateness of the hour, but there’s a chill in the air and me bones are too tired to sleep on the street. Could ya see it in yer kind heart to spare a soul a warm place to pass the remaining hours of the night?”

Making no attempt to hide his annoyance, Thomas said, “I’ve no time for beggars now. I’ve got baking to do. Come back after the morning crowd’s been by and maybe I’ll have a crust for you.” He started to close the door.

“I’m no beggar,” the diminutive stranger said in a haughty tone. “I’m merely a weary traveler denied the comfort of a warm fire in a strange place. Perhaps I’ll have to teach the citizens of this unfriendly town a lesson in friendliness.” He banged his walking stick on the ground, spritely spun about, and walked away into the darkness.

Scratching his head at the odd spectacle, Thomas closed the door and turned back toward the hearth… just as William and the journeyman brought in their first load of wood.

“Father, what was that about?”

“It was just a beggar. I told him to come back in the morning for a leftover crust.”

“A strange time of night for a beggar.”

“True, but he was a strange beggar. A short, scruffy fellow dressed in red looking for a warm place to spend the night.”

“Dressed in red?” the journeyman asked.

“Yes, all red and he had a stout walking stick. No matter; he’s gone. Now why don’t you two fetch some more wood while I add what you’ve brought to the fire.”

The journeyman twisted the ring on his finger and in whispered “Coch Coblyn.”

As always thanks for reading.

Armen

Additional Information

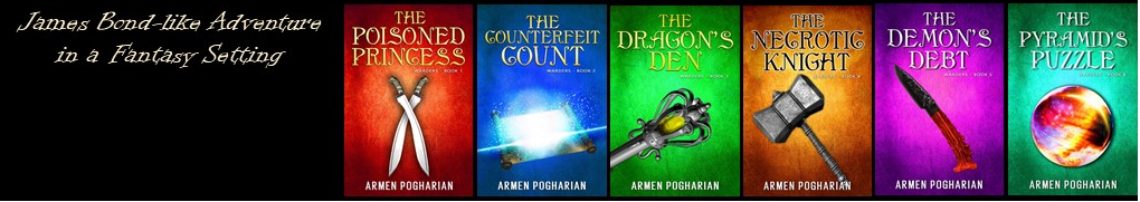

Please visit my website for more information on the Misaligned series.

For my omnivorous readers, here’s NPR’s story about how a meat diet made us smarter.

Thanks for the lesson in history. I loved it. BTW, my own most recent blog entry is due to your efforts. I like your style (…a lesson followed by an excerpt from your book).