The written word, at least for those of us living in the wealthier societies, is nearly ubiquitous. In addition to books, newspapers, and the computer screen you’re reading right now, you can find words wherever you look. They’re on billboards, food packages, cell phones, and t-shirts. Less conventional locations include railcars, bathroom walls, and with the explosive popularity of tattoos, even our bodies. With the exception of clothing (apart from you nudists in the audience), the written word permeates our society more thoroughly than any of our other inventions. It marks the beginning of civilization – without it there are no records or history. Its absence virtually defines the realm of prehistory. Okay, that may be a bit too much, but it’s not far from the truth.

Yet for all of its importance, the vast majority of us take for granted the universal presence of the written word in our modern culture. Sure many know about the ‘invention’ of moveable type by Johannes Gutenberg in 1450. Who doesn’t dream about finding a Gutenberg Bible in a pawn shop? A few may even be familiar with Bi Sheng, whose invention predates Gutenberg by more than 300 years. However the story stretches long before either inventor was born.

The written word’s story begins more than 5,500 years ago as a solution to an accounting problem. That’s when Sumerian trade grew too complex for memory. No doubt cheating became too easy. As their solution, they started recording transactions in clay. It Initially consisted of logograms or symbols relating to words. The system evolved to include spoken syllables. Using a wedge shaped stylus, this cuneiform system of writing supported the languages of Sumer’s successor states. It survived for more than 3,000 years.

The written word’s story begins more than 5,500 years ago as a solution to an accounting problem. That’s when Sumerian trade grew too complex for memory. No doubt cheating became too easy. As their solution, they started recording transactions in clay. It Initially consisted of logograms or symbols relating to words. The system evolved to include spoken syllables. Using a wedge shaped stylus, this cuneiform system of writing supported the languages of Sumer’s successor states. It survived for more than 3,000 years.

The Phoenicians introduced the next major innovation to writing. Centered in present day Lebanon, their neighbors included Mesopotamia and Egypt. They borrowed from cuneiform and the Egyptian Hieratic script to create their own system. Oddly enough, the original Phoenician system did not include vowels. The Greeks added them later. Despite that oddity, Phoenician writing is the common ancestor of most modern alphabets. The Greek, Latin, and Cyrillic alphabets as well as the Aramaic script which begat the Hebrew and Arabic scripts (for frequent readers that’s two successive blogs w/begat).

The Phoenicians introduced the next major innovation to writing. Centered in present day Lebanon, their neighbors included Mesopotamia and Egypt. They borrowed from cuneiform and the Egyptian Hieratic script to create their own system. Oddly enough, the original Phoenician system did not include vowels. The Greeks added them later. Despite that oddity, Phoenician writing is the common ancestor of most modern alphabets. The Greek, Latin, and Cyrillic alphabets as well as the Aramaic script which begat the Hebrew and Arabic scripts (for frequent readers that’s two successive blogs w/begat).

The next great leap in writing was the replacement of the scroll. Scrolls only allowed writing on one surface. This limited information to sequential access (hence the term scrolling). The codex corrected this deficiency. The codex consists of sheets of papyrus, vellum, or paper. A protective cover binds the sheets on one edge. Smaller and more durable than a scroll, the codex offered random access to information. You could open it to any desired section. Its dual-sided writing made it more economical, too. The Romans introduced the codex in the first century. When their empire fell in the fifth century, the codex’s lower cost and better functionality completely displaced the scroll. The codex dominated the written word until the invention of moveable type. Gutenberg and Sheng’s inventions eliminated the need for expensive handwritten pages and ushered in the dominance of print.

The next great leap in writing was the replacement of the scroll. Scrolls only allowed writing on one surface. This limited information to sequential access (hence the term scrolling). The codex corrected this deficiency. The codex consists of sheets of papyrus, vellum, or paper. A protective cover binds the sheets on one edge. Smaller and more durable than a scroll, the codex offered random access to information. You could open it to any desired section. Its dual-sided writing made it more economical, too. The Romans introduced the codex in the first century. When their empire fell in the fifth century, the codex’s lower cost and better functionality completely displaced the scroll. The codex dominated the written word until the invention of moveable type. Gutenberg and Sheng’s inventions eliminated the need for expensive handwritten pages and ushered in the dominance of print.

The In Misaligned: The Celtic Connection, my antagonist uses the handwritten nature of the codex to track down a lost book compiled by a heretical monk in twelfth century Wales.

Excerpt: Again she reached into her pocket, but this time she pulled out an envelope, which she placed on the table. She opened the envelope, took out £500, placed it on the table and passed the bills across to Boethius.

He stared down at the stack of notes and without picking them up said, “I’m afraid you’re a bit short. The going rate is £1,000.”

“Perhaps, but I’m offering you £500 now and the second half after I hear your information.”

“Not too trusting, are you? I won’t pretend to be insulted. Frankly I don’t have a great deal to share with you, but I trust you will find it useful.” He spread the copies she gave him on the table. “With respect to books, there are a few things you need to know about the Middle Ages. Before the introduction of the printing press, all books were written by hand. It was an arduous process that resulted in books being very expensive. Outside the monasteries and abbeys few people could read, even among those who could afford books. There wasn’t what you would call a booming market for them. To overcome this, the scribes added decorated borders, pictures, and initials to their books, turning them into works of art.” At this point he paused.

“I said I wasn’t an expert on the Middle Ages, not that I was illiterate about them. I hope that you’ve got more than that, or I may need to request a refund,” she said, with just a touch of anger in her voice.

“But of course, I simply needed to lay the foundation. You see the illuminations are unique to each manuscript or book. Rather like a fingerprint. So it’s possible to identify when and where a book was produced. In some cases you might even be able to identify the specific writer of the book. All you need is an expert who can match the illumination to a known reference.”

“And if there is no known reference?” she asked.

“It’s still possible to get some information from things like the composition of the ink used in the book, the fibers in the book’s pages, the style of the artwork, et cetera. However, that won’t be necessary in this case.”

“You know where this book was written?”

“I can’t be certain, but the illuminations on these pages are very similar to those found in Llyfr Du Caerfyrddin, the Black Book of Carmarthen. The Black Book dates from the mid-thirteenth century. It’s a sort of compendium of poems with everything from odes of mourning and praise to poems about the Arthurian legend. It’s the oldest known book written in Welsh. It’s a national treasure and is part of the collection of the National Library of Wales.”

She was familiar with the book, but like most serious Arthurian scholars, she dismissed it as a valid source about the legends because it was written after Geoffrey of Monmouth’s romanticizing of King Arthur. “I’m happy for the Welsh, but I don’t see how that helps me find Cyfnodau.”

“As I said, these copies are similar, but not quite as well developed. I suspect that it predates the Black Book, which makes it a very valuable item indeed. Of course you already knew that. The key is that the Black Book was written in the Priory of St. John the Evangelist in the town of Carmarthen.”

“So you’re suggesting that the Priory would be a good place to start my search?”

“It would, if you could travel back before 1536,” said Boethius with an air of superiority in his voice. “That’s when Henry VIII used his authority as the Supreme Head of the Church in England under the Act of Supremacy, to dissolve the monasteries of England, Wales, and Ireland. He confiscated all Church property, redistributed some, but kept most for the crown. It got him out of quite a pinch with his bankers and freed him from the final vestiges of Papal authority.” At the last Boethius let out a few thin raspy chuckles sending a small chill down her spine.

“I’m not sure what you find so amusing, Boethius. I’ve paid you £500 for information that I suspect one of my enterprising eighth grade students could have dug out of the internet. If you want the other £500 you’re going to need to give me something I can use.”

“Yes, I suppose you’re right. As I said, most of the church lands went to the crown or nobles, but before the transfer occurred many were looted.”

Impatience clearly beginning to show in her voice, Ms. Morgan said, “Again, I’m not sure how this little history lesson helps me.”

“If you would stop interrupting me, I would get there faster,” said Boethius, although in truth he was deliberately dragging things out. The more he irritated her, the better chance that she would slip up. He might even learn the identity of her buyer, although he admitted to himself that was probably too much to ask. “As I was saying, many were looted before good king Henry got control of them. Animals slaughtered, precious metal items melted down, clothing reused, but the books were a different matter. They were clearly valuable, but even in 1536 literacy was not prevalent among commoners. So the books that survived the looting ended up in the only place that valued them,” after another pause for dramatic effect Boethius said, “a university. The trouble is finding out, which university. The Black Book found its way to Bodleian library at Oxford, from where it was eventually returned to Wales. So since your copy of Amddiffyniadau obviously survived the pillaging and came from the same Priory as the Black Book it’s a reasonable bet that if its companion survived, then it too found its way to Oxford.”

“So you’re saying all I have to do is go to Oxford, hoping that they’re ignorant of what they have, search through more than ten million volumes, find Cyfnodau and somehow take it without being noticed?” said Ms. Morgan in her most sarcastic voice.

“I suppose you could try that, but I doubt it would work. As you say, your best hope is that they have the book, but are ignorant of its value. If that’s the case, it’s probably not among the volumes available in the library. It’s more likely in one of their offsite storage facilities. As a legal deposit library, the Bodleian receives a copy of every book published in Britain and Ireland. The books have been coming in faster than they’ve been able to add shelf space. Over one and a half million less used items are in several off-site storage locations. Because they’re the most susceptible to environmental damage, the oldest items are stored in an abandoned salt mine in Cheshire. Now was that worth the balance of our transaction?”

As always thanks for reading.

Armen

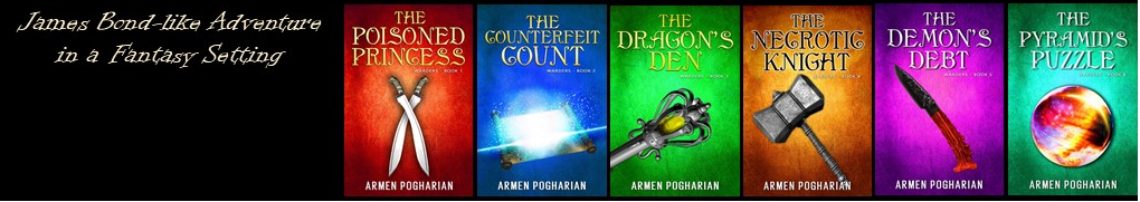

Please visit my website for additional information about the Misaligned series

More Information about Writing

Brief (6 minute) writing video from the British Museum for younger readers.

For those who like Powerpoint here are some slides

Reread your 8/13 blog on the written word. Still awed by the research you do.

Missed this back in August. I love the amount of research you do to prepare your blogs. The whole history of communication is just fascinating. As more and more archeological discoveries are made I also find it fascinating that we are finding evidence to substantiate much of the so-called mythology of the classical times. (ex: Troy, The Flood…)

Thanks, Rick. I don’t post as often as I’d like, so I need to make them count. To be quite honest, I often read something interesting, decide to learn more about it, then think – hey that might be an interesting blog.